Audre Lorde made me angry. Audre Lorde made me think. At first, I thought she was picking on me.

I’ll never forget the day it happened. I was taking the subway home after work. It was hot, sticky, and crowded. I was in a rotten mood.

Then I saw something that made me smile. On a placard high above my head was the New York City Transit Authority’s “Poetry in Motion” series. The excerpt was from a poem called “Coal.” It was written by the great American poet Audre Lorde, one of my former professors at Hunter College.

I felt proud, then immediately sad — at the end of the poem, along with the year of Lorde’s birth, was the year of her death. I hadn’t known. Although I hadn’t consciously thought of Lorde in years, if I were really honest with myself, no one taught me more about writing than she did.

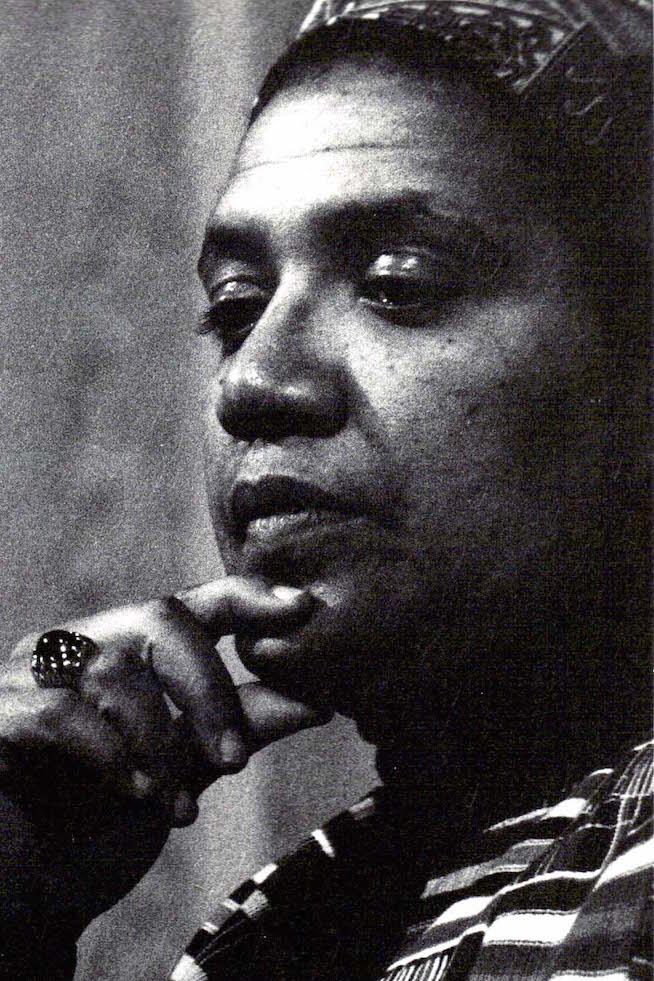

On the first day of class, Lorde and I immediately clashed. Why was she making us describe ourselves in one sentence? This had nothing to do with poetry. When I snarkily suggested that Lorde do the same for us, she stood in front of us boldly, hand on her hip, the mastectomy for which she refused to wear a prosthesis defiantly obvious as she neatly outlined herself for us: “I am a black, militant, lesbian poet.” As if silently challenging: "And what are you?"

Over the semester, I tried to find out what I was, and Lorde tried to help me. She absolutely refused to accept my response to her harsh (but fair) critiques: “But that’s just the way the poem came out.”

“Poetry is not a bowel movement,” Lorde explained to me calmly. “It doesn’t just come out.” She would shake her close-cropped, salt-and-pepper head. Even her heavy, hand-carved wooden jewelry would clatter in disagreement with me. Patiently, Lorde showed me that pure, true poetry had to be coaxed, poked, cajoled, and gently wrestled into shape.

Lorde revolted against everything: from hypocrisy to fine-point pens. Once, she scribbled Please write with a pen I can read next to a drawing of a pair of tired comic-book eyeballs. When I got something right, there was a triumphant Good with two or three exclamation points. When I got something wrong, she prodded, Into what is this experience anchored? or a resounding No.

Audre Lorde made me angry. Audre Lorde made me think. At first, I thought she was picking on me. Didn’t she realize that I had five other classes and worked part-time? Then I thought she just didn’t like her white students. (Little did I know that her longtime partner, Frances Clayton, was white.) But I soon learned that Lorde didn’t dislike anyone. She only sought the truth — in poetry, in life, in me.

We were as different as two women could be. I was 21 — a Catholic, heterosexual college student, living at home in Brooklyn and still trying to discover who I was. At the crossroads of her life, Lorde knew exactly who she was. She was waging a war against cancer and sharing an old house in Staten Island with her kids and partner. But maybe we weren’t so different after all.

Our creative sparring evolved into something of a game. Lorde knew that I knew that she wouldn’t tolerate lazy excuses for prose, but I kept testing her. I can still see her now, her voice strong and melodic, her small, rectangular glasses perched at the tip of her nose, a bright, hand-woven tunic loosely floating about her body, the soft essence of patchouli surrounding her, green marking pen in hand. And her eyes. Those strong, black, unwavering eyes that burned right through to the core. Like coal. Yes, just like coal.

And so, that day on the Brooklyn-bound F train, I read Audre Lorde’s poem and cried. I was glad to have known her. I was sorry she was gone. I only wish I could thank her.